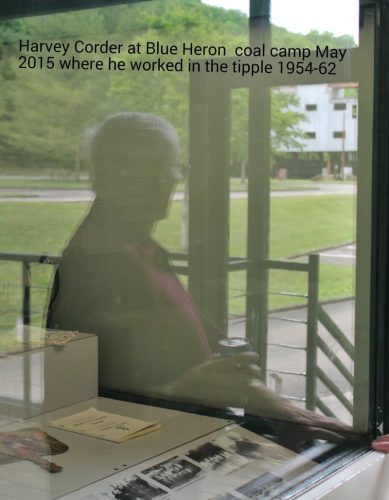

Today’s post is second in a series written by Ron Stephens about his father-in-law Harvey E. Corder and the Blue Heron Coal Camp located in Kentucky. You can see the first post here.

Eighteen tipple reflects over my shoulder in wavy, watery gray. It is still big and strong, still casting a dark bar of shadow northward over the camp. The Company built it to last a hundred years, long enough to mine all the coal they thought they had. It did stand the natural storms, more or less. They sunk the concrete pillars deep in the ground below and raised them up above any chance of overflow by floodwaters. The top level making the bridge over the river to the mines on the west side is in the treetops. They designed the steel to meet high over the center of the river in clear span, cantilevered from a concrete pier on each bank. Out in the middle, under the tram track, two steel pins align the halves. The Park people have painted them red. After the Park came in, they discovered the river had undercut one of the pillars, throwing the two halves out of alignment. How long it might have kept standing is anybody’s guess. Anyway, Nature never took it down.

I spent a great deal of my life here in this camp, over in old Barthell, up on Worley Hilltop and out at the Coffey Holler. So did Dad, my brothers and my nephews. Once upon a time, I was on that tipple every working day and my brother Calvin was down below at the bathhouse. Now my blurred reflection is yet another parable, a kind of ‘glass darkly’ like the Bible speaks of.

It seems odd to me now that I spent so much of my life so close to here. Seems like some choice I made somewhere along the way in those years would have taken me away and kept me away. Time after time I would leave, for one reason or another. Another chance, another choice always brought me back. These places tie me to them, Eighteen, Barthell, Worley, Worley Hilltop, Coffey Holler, Mine 16 and Co-op. I don’t even live here anymore but the ties remain. A few of them are like the steel rails, strong and lasting. Most of them have become like the first spring green, tender and beautiful but faded and soft.

All the pieces fit together best here where I stand. This is the once-upon-a-time place of Faith and behind me is the long-ago place of Works. All my time I have lived in that place of mixed faith and works. There was always some things I could not do and always some other things it was not my business to do. I had to have faith for both. When I was young, I thought as a child though. I believed I could not change what would be. It was all in God’s hands. I loved cars and I loved to drive fast, telling myself I would not die until my time. Over the years, my thinking changed some. I had to learn there was always going to be some things that were my responsibility, for me to work out. I could ask for help but I could not expect the Lord to do my part. In this middle is the place where I’ve always struggled to know which was which. Sometimes I learned later on that I had made the wrong choice. Others I may yet find out. Some things you have to accept and let them go. What has passed beyond redemption is one of those.

The town of Eighteen has passed. Once upon a hopeful time, it was a living community, here in this narrow cliff-bound holler of the Big South Fork of the Cumberland River. The post office name was “Blue Heron” because the postal service insisted on having a name. I do not know where it came from. Maybe somebody saw one on the river. Maybe it was being called Blue Heron even back when I was a boy, before they built the tipple. Anyway, Blue Heron was really just the name of a cubbyhole in the corner of the store. We always said ‘Eighteen’ because it was the eighteenth mine the company opened. The camp didn’t live long after they built the tipple, only about twenty-five years. I guess that was why we called them all ‘camps’. The Park people say that anyway, telling us what we thought. I do not recall thinking about it then but whether logging or mining camps, they came and went, an uncertain dwelling place. The Park people say there were twenty-two houses here altogether. I guess that was probably a hundred to a hundred and fifty people or so. That was before my time working here. A high number like that would have been back when they were still hand loading and needed a lot of men. When I came to work here, everything had switched over to the mechanical Joy loaders and there weren‘t that many houses left. The Company had started selling them off for salvage. The camp was already drying up. People didn’t want to live here much even before they built the road in 1948. After that, few would live down here.

I don’t reckon Eighteen camp was much different from a lot of others. It strung out down the river from the tipple, about three-quarters of a mile long but only a few hundred feet wide. The flattest land along the river flooded in spring and stayed in woods. Not far above high water the slope got so steep and rocky it was not much use. They cut mine props and other timbers from there at first. I remember it in my day as cut over and mostly scattered bigger trees. Finally – forever hanging over everything – was the great sand rock cliff. The camp awoke in its shadow and lived in it until mid-morning. I went to work in its blue shade and when I had time to look I’d see its shadow backing down the other side of the river and inching down the tram tracks on top of the tipple till the sun climbed over the rim. In the fall, I was leaving about the time the shadow from the other side of the river was falling across the tracks. In the winter, the whole camp was already in shadow when I left. Fall and winter, I chased the light, climbing out of the holler, glad to get on top and catch up with it again before night fell.

Mining took the best of what ground there was. The mainline tracks went in first below and then they put in the mine tramline, repair shop and entries above. Houses fit in on whatever the river, the mines and the rocks left not taken. Even the mine superintendent’s house had about a thirty-foot tall rock right out the back door with the tracks about forty feet away out the front. That was why the camp was so long. It took all of that distance to shoehorn houses among the rocks. In the beginning, the best houses were white-painted siding with green trim, the Company colors. Before long, the sulfur smoke from heating with coal and the coal dust from the tipple turned them dingy yellow-gray. The pine board-and-batten houses fared better. They weathered a dark brown but the sun pulled bright blobs of yellow pine rosin out of the knots and yellow streaks like runny eggs out of the heartwood. From the top of the tipple, when I was here, I think I could see every remaining house all the way north to the road out.

For almost the first ten years, there was no truck road. Main Street was the tracks and ’cars’ meant the train. By the time they put the road in there was only one possible place for it, below the railroad. That put it into the reach of floodwater sometimes. A few times, I have seen the water reaching all the way across the road in the lowest places and lapping at the tracks. It made my skin crawl to drive through the edge of that muddy river even when I knew it wasn’t deep. It was just not like driving through a mud hole. It was live water and I never forgot I was driving through the river. Somehow, I felt the weight of all that water from way down in Tennessee rushing past. The river never cut us off and the tracks never washed out but we were never sure it could not happen.

Nobody had really planned for the church and store. They came along later. The store got started because people would ask for the train to bring them things and that turned into a store. The people in the camp paid for the church with donations and built it themselves. Both the church and the store ended up below the road, in the edge of the floods. The church was like an old lady holding up her skirts, built up high on concrete blocks to get well above the water. But they would still have to shovel the sand out of the basement in some years. The boardwalk in front of the store was just a couple of steps above the road in front but the back was on high stilts. Floodwaters ran all the way under the store. The water never quite floated it off but it was a near thing a time or two.

I remember there was a bathhouse with hot water at Eighteen. Not many camps had that and the miners here struck to get it, back before my time, even before they built the tipple. Working on the tipple, I tried to beat the miners to the showers. Usually I could. We changed clothes in the bathhouse before work, putting on our old grubby working clothes. The wives hated to wash them because they had to wash them separate. A few of the miners simply started with new clothes and wore them unwashed until they threw them away and started over. I never did that, could not afford it.

On one end of the bathhouse was the lighthouse. The lighthouse man kept the miner’s lights there. My older brother Calvin had the bathhouse and the lighthouse job here for about four years. He kept the boiler fired to have hot water and checked the charged miner’s lights out at the beginning of shift and back in to be recharged at the end of shift. He is still living, but his sight is not good and like me he is worn down.

—-

Be on the lookout for the next part of the series “Reflections.”

Tipper

Subscribe for FREE and get a daily dose of Appalachia in your inbox

I found many statements to be profound and certainly worth deeper thought, on my part. We all should probably give some time each day to reflection, in regard to the struggle “to know which was which”. Great thoughts and writing. Thank you for sharing.

Again, I am late seeing this post, but this time I must comment on Ron’s story. When I was reading part I, I realized I had been to this locale several years ago on the train from Starnes! I was intrigued by the museum, the pictures and the miner’s houses at the top of the mountain built along the narrow, rugged ridge, wondering what it must have been like to grow up there. I’m glad to know it was more than just a few houses, but a real community, with a church, store, and post office.Thank you, Ron, for sharing this unique and personal window into the past.

Another Winner! Can’t wait for more!

Tipper,

When I got out of High School, after I was married, my wife Paula Fish went to see Frank Fish, with his wife, Colleen Wright Fish. We made it to Coalwood, West Virginia where he worked in an 8′ hole in the ground. The Walker, Dude Hardin offered me a job. He had trouble with some boys from Bryson City, to throw him down the Shaft, that is why he carried a sawed-off shotgun everywhere he went. He stayed at the same Motel as we did, and Dude told me it opened up to a City, after about a 1/2 mile down.

I took one look at the hole and decided that’s not for me. I’m not sure of the purpose of the Shaft, but after you got down there, it was to carry Fresh Water and Sewer to the town of Coalwood. …Ken

Thank you, Ron Stephens, for one of the best writings I have read on a description of life in a Coal Camp and work at the mine. Rocket Boys was a dramatic depiction of children growing up in a coal mining town of Coalwood. While interesting, it missed an opportunity to show accurate depiction of true life in these coal mining communities. Hard to believe, but my early childhood memories of living in a coal camp are among my favorite. It was the feeling of everybody being family and looking out for each other. Borrowing was extremely common, and kids scattered all up and down the creeks and mountainside playing. Baby sitters were easy to get, and I remember staying with a variety of neighbors if my parents needed to do anything. There were no helicopter parents which allowed most children to run free and learn independence young.

I was so pleased later in life to work in the that coal mining county of McDowell I loved so much. Even all those years later the people remained kind and giving. They had a sharing that is unusual in this day and time. Anthony Bourdain made a visit for his show, and he described it best when he said the county showed “everything wrong and everything good about America.” The poverty and health conditions from years of hard work are there, but the people are so friendly and giving. I look forward to more of your writings, Ron.

He paints a very detailed picture of a snapshot into his life. A hardscrabble life can be in anyone’s past but their later reflections on it and how it shaped and molded them can be quite a story. We sometimes only hear about the bad people but there are hundreds of good honest hard-working God fearing people who are really the fabric of this country.

What a wonderful story!

A life I cannot begin to imagine. Hard work and long hours. It was their life and their homes. I guess they didn’t think too much about it. We all live the life that is given to us to live and do the best we can. Family makes it all worth while.

Thanks Ron, for this little window into our past.

My family’s history is around the paper mill in Canton NC. It was hard work and long hours too.

Wonderful story Ron. Me thinks you could have been a writer if you had so chosen.

I enjoyed the whole story but to use your word (struck) I was struck with paragraph 4. Quote, ” In this middle is the place where I’ve always struggled to know which was which.” How true in my own life.