Today’s post is the final piece in a series written by Ron Stephens about his father-in-law Harvey E. Corder and the Blue Heron Coal Camp located in Kentucky. You can see the previous posts here:

They burned the coal we loaded out of these hollers. It is all gone long ago, vanished into heat, ash, and smoke. It did its part in its time to power the wheels of a nation. While Eighteen was running, we did not know who bought it or burned it or for what reasons. Maybe it melted iron or heated schools or hospitals. It was not important to us to know. If we even thought about it then we just thought the country needed it; something of value for everybody, like it was for us. Whoever used it did not know us or think about us either.

Mostly I just mosey around here now, kind of aimless, thinking back and pondering on my own life and life in general. I am looking for something every time I come. I am not sure what. I just feel something missing, as if I have lost something here and if I look hard enough long enough I will find it. I’m reminded of the man who had drawn his pay in scrip and was walking up the Barthell Rocks. Somehow he dropped those brass scrip pieces and they bounced and rolled down that long slope of rock and into the brush below. As far as I know, none of it was ever found and it is there yet.

I keep thinking about how we come and we go. We do not leave much sign of our passing. I came and I will be going soon. I guess back then I thought we – all my generation – would be more important somehow. But I never quite figured out what I meant by ‘important‘. All I know is the four most important things I’ve ever done was preach the gospel, pastor churches and be a husband and father.

I dread to come here to this old camp in some ways. There are so many memories. Yet I love to. I cannot stay away. My mind runs in ways here it does not anywhere else, thinking about what was. I miss all that is not here, the things the Park folks cannot re-create. But I mostly love the memories. I’m glad there is an effort not to let those memories die, even if to us who lived it they leave so much out. Almost ever time I come, on my way out I think maybe I will never come back. There are ghosts here and they haunt me. One of them is the man I was then. One of them is the man I hoped to become then and never quite did.

I miss most the people I knew who are now ghosts themselves. They are still real to me with all their human emotions. They were the spirit of the place and, as the Bible says, the body without the spirit is dead. They knew joy and fear and hope, tragedy and triumph. They struggled and planned and strived. Among them there were ugly and plain and beautiful, wise and foolish, strong and weak. They were real people. I want you to know that. I want you to remember them that way. It is important because one day it will be your turn, no matter where you live or what you do. Change will pull the rug out from under you as well.

In the display cases are black-and-white pictures of many of the people that were here. They have even made a few of them, like Cack, into life-sized cardboard cutouts. (I am not either one, not here at all. Neither is my brother Calvin.) They are a kind of ghost as well, even the few still living, because they do not appear as they are but as they were in the long ago. I remember those now dead as living. I remember – though it is fading – their face and form, their grace of motion, the sound of their voice and their little odd ways of doing. For some of those I remember you can push a button and hear their recorded voices at each of the ghost structures. I hear other voices, not on the tapes, recorded only in my head, telling and re-telling other stories. Looks like I will take them with me when I go. Those are ghost memories to me now. They are sweet but painful. Sometimes I have to cry a little inside and sometimes I laugh. Those people tug at me more all the time to come be with them. They are treasures I have laid up.

I remember ‘Cack‘, the general superintendent. He was a good boss and the men liked him. He grinned all the time, no matter what was going on. He’d come out of the mines black as coal himself with only his eyes and teeth shining. But he still had that wide grin. Nobody, not even the big bosses, could get ahead of him. He thought the quickest on his feet of any man I ever knew. I helped ordain him in later years and he was pastor of several churches. I don’t think he could whisper, everything he said was loud. In my mind, I still hear his yell.

“Hey Calvin!”

Answer, “What have I done now?”

Cack’s reply, “That’s just it. You ain’t done nothin’.”

It was just going-on, did not mean anything but good fellowship among men who knew each other well. We were a good group. I guess there must have been some cross words but if there were, I cannot remember. We all knew what to do and how to do it. We would help each other, no tearing someone else down to look good.

I remember the time one fella was supposed to be watching the belt up the outside of the tipple, the one used in oiling the stoker coal. Guess he got too warm sitting in the sun on the south side of the tipple. Anyway, he fell asleep and one of the big bosses caught him. He did not wake him up; just said in that deep voice of his, “Sleep on, bud. Long as you sleep, you got a job. When you wake up you ain’t got one.”

There are better memories besides of so many other men. They are all gone now. In their time they were good men, hard workers, honest and good friends. I miss them.

Nothing here now is like it was then, not in looks, sound, or smell. Even the air tastes different. The tourists come to look but I doubt if it ever really touches them. Except for old coal miners or those who lived in a coal camp, none of them can see what I see, what I have seen. What does it cause those folks to think? Or do they? I’ve heard the kids sometimes, “There’s nothing here.“ or “This is boring.“ That hurts. I wish I could, or somebody could, make it real to them as it still is to me. They do not know who I am; that I worked here. They walk beside me but I don’t say anything. I do not know if they‘d care to hear it. Very few ever talk to me first. I guess in a way I’m a living ghost.

The Park people asked me once to guide tours here. Maybe I should have tried to make it real doing that, I don’t know. But I can’t hardly hear anymore, working so many years next to the shakers did that. They would ask me something and I wouldn’t hear them at all or would not understand. I would feel stupid and I hate that. I knew they would want me to work weekends and it would interfere with church. I couldn’t feel right about doing that when I really had a choice. I have not always had one. A few times, I have been here with someone else and when I’m talking to them, other people gather up, wanting to hear me.

Everywhere you looked then if you could see the dirt it was a combination of powdered coal and slate. Slate is a flat gray, sort of like pencil lead or a rainy November sky. Coal can be a dull black if weathered or a shiny black on a new break. After it lay out in the weather, our coal would have a yellowish-white sulfur bloom. Now there is no exposed ground. The Park covered it all up. Now there is green grass, pavement, clean concrete, trees, brown leaf mould and green plants. No coal miner in my day ever saw an operating coal tipple that looked like this one does now.

I remember the tipple all rust streaked and battered. The windows had iron frames and the iron wept brown rust streaks down the side of the gray tin. Especially before the Park came in, it looked really rough, mostly rust by then after nearly fifteen years of neglect. All the window glass for the office had been broken out. They fixed most all of that. Now all the iron has rust-resistant coating and there is no more weeping, not rust anyway. The tin is new looking but not shiny. I guess they didn‘t want shiny new.

The coal cars are one of the biggest changes. Back then, they were a faded brownish-red, like dried blood. Rough handling had banged and bent them. The paint was scraped and flaking. I guess most of them had survived thousands of miles through all kinds of weather. The ones we saw were always rusty and marked all over with chalk or paint. Now the ones on display here are uniformly dull black, without a scratch. The stenciling is snow white and sharp, like their first day on the job. These on display probably never have hauled a lump of coal. They almost certainly never will again.

Even the tracks are part of the display. I remember stained and oil-soaked gravel ballast between the rails. The crossties had a center scrape mark, all splintered up from things dragging under the cars. Those ties were weather-cracked and faded to a chocolate brown or a brownish-gray. Now the ballast is unstained sparkling white, not rough gravel at all but something expensive. It looks like white marble chips. These ties have no seams or splits. Their edges are sharp and square, the same uniform dull black as the cars, like no tie I ever saw back then.

Inside the tipple now are bright bars of sunlight, clear air, glimpses of blue sky with white clouds and green treetops. The girders stand out with sharp edges. How different in my mind! Then thick dust covered every flat surface. We worked in a haze of dust rising from the screens, the belts and the cars. We ate dust and breathed dust. It had a brassy, sulfur-and-grit taste and a sharp metallic smell. On hot summer days, the smell of creosote mingled in to make a smell for which there is no name, just a feeling. By the end of most days, we were as filthy as the miners were, maybe worse.

It is quiet now, and still. We never knew either. We lived in noise. There were too many sounds to remember them all now. Our day started with the horn blaring the warning to get clear of the belts and shakers, quickly followed by the odd, rising peeechuuunnggg whine of the electric motors spinning up. Soon there was the rumble and roar of the shaker screens and the conveyor belts. Woven in and out and through was the hiss-swoosh of the loaded mine cars and the rattle of the wooden decking as they came in to dump. When they hit the trip lever, there was the echoing bang of the car doors slamming open, metal against metal, and the racket of coal falling into the hoppers, Bang was the sound of the sudden slam of a piece of rock against the back board over the waste belt. Down below the coal fell into the cars first with a clatter, changing to a semi-musical clinking and hiss. When we let the brakes off on the empties, there was the sudden pssssst of compressed air and the squeaking groan and creak of the moving coal cars, the low, steely, ground-shaking rumble of wheel on rail. To those who did not know, there was only a dull roar. We could sort the sounds and operate by ear. We knew what it meant when a sound was not right or when one that should be there was not.

We were young, thin and quick, those of us who picked the waste and brought down the cars. The belts were never supposed to be still more than necessary as long as there was coal in the hoppers. At least we acted like it. It was a matter of pride with us. From high up in the control cab, the tipple foreman would bump one of the belts, stop-start, stop-start. That was our signal to run that full car out and an empty in.

It was a race.

Two of us ran down the very steep and very narrow stairs, splitting up at the bottom. One unhooked from the winch, released the brakes on the full car, and let it roll down the inclined track. The other uncoupled the next empty and released the brakes. Mostly they started rolling on their own or we could nip a bar under the wheels until they started. Whoever was available caught them with the hook on the electric winch cable, playing them like a fish to stop under the belt exactly right. We did as much as possible ‘on the fly’ as if the belt did not really ever have to stop. There was danger in all of it, the running, the rolling cars and the straining cables but we weren’t afraid. We were confident and gloried in our skill. We ran around the top of the cars on that four or five-inch wide lip like squirrels, laughing at the danger. Only once did I fall, but I felt my balance going and jumped into the car, burying to my knees in stoker coal. The men had a good laugh about that.

I have seen so many changes in my time, too many. There have been way more than I would ever have guessed would come. Many of those I did not see coming. Looking back, I don’t see how I missed them. Most any time along the way if you had asked me if I would have believed things would be as they are now I would have said, “No.” Seems to me the future takes us all by surprise, no matter how smart or prepared we think we are.

Maybe a natural life span is too long to avoid great changes. Maybe it is not long enough to understand them. I do not know. Sometimes I feel one way, sometimes the other. Today my life feels way too long. I am eighty-four. I worked here for eight years over fifty years ago. Fifty years! Half a century. I’m astonished every time I remember how long it‘s been. I never thought this tipple would shut down, much less that this whole river country would go into a Park. I never thought mining would end. I should have guessed some of it. I already knew that fifty years was just about how long old camp Barthell lasted. One of the things I have finally come to know is that there is a lot of wisdom hidden in plain sight, seen but not understood, like the red pins on the bridge.

I guess the Park folks think now the Park will be here forever. Seems every generation spends the biggest part of its threescore and ten thinking that what they know is what will always be. I did myself for a long time. I don’t anymore. I have not seen it happen, not anywhere about anything, not even in church. The gospel is the same but the people are not because the times are not.

Took me a long time but I finally realized it has not been just me. It is every generation, every job and every place. Things change. What we grew up knowing goes away or something takes it away, one way or another. That is what has stayed the same.

I have too much memory. At least I have my mind, unlike many I have known. I am the last but one to have some of those memories. Cack’s son, Don, is the last besides me who worked on the tipple. I’d like to talk to him once before I go. All the others are gone and I will be before long. That is another big change soon to come, when all of us who can remember are gone. I would like to pass on what I know of how it was. I am just not altogether sure how to do it or who cares to know. Generations don’t learn much from each other. I have lived that to, from front and back. That is another of life’s puzzles.

Eight years, from 1954 until 1962, that was my time on Eighteen tipple. I thought I would be here until I retired or died or just plumb give out. The Company said they would run five hundred million tons of coal through this tipple. Instead, I heard we ran about two hundred and fifty thousand tons, first to last. Had they known that, they would not have built Eighteen tipple. My life might have taken a very different turn.

Back then, they didn’t core drill ahead before they faced up a seam to start a mine. If they had, they would have known the seams on the west side of the river would pinch out. Instead, for miles upriver they opened up in #2 seam time and again. Each face looked good at first, only for the seam to rapidly narrow down and pinch out to nothing. Each time they had to decide: Should they tunnel rock hoping the seam would open up again soon or quit and go somewhere else and try again? Their choices were limited. Behind the camp was only a narrow hogback ridge in a big bend of the river. They could only go one direction that way. As it was, they went about two miles up the river on each side and a mile down the west side, trying to make it work.

I loaded out the last three cars ever loaded at Eighteen tipple, scrapping up about fifteen tons on the very last day. It was not my usual job. But we were down to a skeleton crew, just tidying up a few loose ends. It was not about production any more. I think that was just before Christmas in 1962.

When the belts ran empty I watched them run for a while, knowing it was all over, dreading my final act. I rested my hand on the big red master STOP button. When I pushed it, I looked away, out on these green hills. I did not want to see. I heard it and I felt it through the steel. There was that peculiar mixed sound of click and clunk and fading hum as the contacts gapped and the motors spun down. The rattle of the screen stopped. The belt ground to a halt with its sliding scrunch and squeak. Silence fell, hard and final. The swirling dust began to settle. It was not even twelve o’ clock. That blue day is one of several that haunt me, like the day our boy Ronnie Dale died.

I wish I could describe the feeling that goes with that kind of ending; the feeling you get when you know everything has changed and nothing will ever be the same again. I have had to get used to endings. I have had my share. If you have lost someone, you’ve tasted it. I wish there was a way for you to have my feelings, just a little – but without the experience – so you could know what it felt like. I don’t want you to feel all of it, just enough. You will not really understand any of this if you have no feeling for it. Chances are life will get you there, sooner or later. I think I wish you could miss it. I am not sure. But anyway I know you cannot.

I understand now what I did not then. My kids and grandkids don’t care as much as I do. It isn’t reasonable that they should and it is unreasonable to ask. I was still that way myself until recent years. I never felt sorry for Dad seeing old Barthell shut down; never thought about it. I was too young still. He was gone as well not so long after I came to work here. We all serve our generation and pass on. He did, I have, and they are. So are you. That is how it goes.

I am driving back out the bent and twisty road, climbing up into the light, when I realize something. I am never going to decide how important my generation was. And neither has any other generation. Things change, generation to generation. Neither will you. Each one has its endings. Each one has to reconcile itself to them. It has always been that way and always will be.

We live and die in the fellowship of the human condition. God help us.

I returned, and saw under the sun, that the race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong, neither yet bread to the wise, nor yet riches to men of understanding, nor yet favor to men of skill; but time and chance happened to them all. Ecclesiastes 9:11

I hope you enjoyed Ron’s series as much as I did. So interesting and inspiring to look back through someone’s life and the struggles they faced.

Subscribe for FREE and get a daily dose of Appalachia in your inbox

Wow , deep stuff , deep and precious… at the beginning of his time on Eighteen tipple in 1954 I was 2 years old ….yet I was able in my generation to get to experience the usage of coal, a coal stove, a coal cook stove ….I remember them coming and dumping a big pile of coal in my granny’s yard, I remember the warmth of the heat , I remember sound of it burning ,the smell of chimney smoke and the soot on the snow in winter….so grateful to have had the privilege to read his sharings…listening , seeing through his minds eye ,learning through his heart’s musings, thankful to have gotten to glean in his field, and then to beat out the grain from the gleanings to process, and then be nourished by. Way down deep. Thank you for your sharing.

Please tell Mr. Stephens and Mr. Corder that tourists do appreciate the camp! We visited two summers ago with our son who was 12 at the time. We took the Big South Fork Scenic Railway in and toured the Blue Heron camp. We hadn’t known what to expect, but the camp left a huge impression on all of us. (In fact, I still recommend the trip to friends.) We found the stories in each of the structures incredibly moving. I personally feel that the Blue Heron Camp / Park is incredibly important to America. It tells a vital and vivid story of American history that people need to know. And it is important that our children understand how people from all over our country made the lives we lead possible. The people that worked these mines and the families that grew up in the camps gave so much. And it was their efforts that powered America for years. Sadly, they got very little in return for all they gave. I only visited the Blue Heron Camp/Park for one afternoon, but the memories that we took away with us have lasted–and will continue to last in our lifetime.

Tipper,

I liked Ron’s stories of Life when he was a young man, he explains it so well. My friend Jesse Allen, husband of Myrtle Yonce nearly all of his life, and as soon as he finished a job, he’d head for another. He told me he worked in about every state, but he talked alot about when he worked in New York in the Cat Skill Mountains. I was amazed at how he remembered all the employees names and where they lived.

My wife’s uncle was in Bakersfield, California in a tunnel. He was a Marine and wouldn’t take nothing off nobody. (Ron reminded me of this and it tickled me). Anyway, Roy hadn’t been on the Job very long, and it was Loud in there, and his Boss told him what he wanted Roy to do. Roy Knocked him down, and told him not to storm at him, he could hear well.

Roy Wright lost his wife Shirley a few years ago to Cancer , and he came to my shop about every couple of weeks. …Ken

Never a better portrayal of life as a coal miner or as one who was once part of a coal mining community. I would please ask that some way these reflections are made a part of the archives of that state or somehow preserved. `Thank you Ron for such a descriptive post to help others understand a part of our history that soon may be no more.

I still recall Dad speaking of “Spud” his boss and telling of how they quickly saved the life of a man who had managed to fall into the dump truck full of coal. When we moved away Dad still drove the numerous miners on his route to work. As crazy as it sounds he had rigged a very small pot bellied stove in the middle of the camper cover which he stabilized and even wired door so could not fly open. The small fire kept the miners from freezing. So dangerous, but that is how they had to roll in those days. Not many rules or safety laws then. That was in the late 40s and early 50s. I too am haunted by something that can never again be. Why are the train tracks so empty, and no more familiar train whistles that’d can be heard for miles? People were and are still real to me, and I have realized most all these dear people are gone. The Potters, Snows, Broskeys, Mitchems, Johnson’s, Halls, and the teacher, Jodi Boston are no longer here. On a lighter note I do believe there will be a wonderful reunion one day. Maybe that is what we keep searching for in our past and what our ‘’Maker’’ actually has in store for us. That will be some reunion!

Thank you for memories of life!

I want to thank Tipper for posting Harvey’s story and each of you who found something of value in it whether you commented or not. The comments were gratifying, not to my ego so much but moreso that it was meaningful to you. (I suspect Tipper often feels that way.) As many of you realized, it was meant to be mostly about change. We all experience it. The biggest difference in Harvey’s case is that there is a memorial of what was which most of us will not have.

Harvey thanked me for having written his story. He told me he took the hardcopy out every now and then and read it once more. But since it was written his eyesight has gotten much worse and it is a great struggle to read at all. He called recently and wanted me to read part of Genesis 22 to him. And Calvin has since passed, going from being alert and feeling well over just about two weeks. The changes keep coming.

I was never a coal miner, just to be clear. I left the county, in part to avoid the mines but it has made me homeless in spirit. Dad was a miner. He didn’t want to be. But it was what there was. He was paralyzed in a rockfall at the Justus when he was forty-seven in October 1974.

I know a ‘real’ miner can spot flaws in what I wrote and could tell it so much better. I am sorry I could not. It also troubles me some that perhaps without meaning to I have hurt someone by getting too close to wounds of their own. I am caught like Paul was in repenting of that while yet not repenting of the larger purpose. I confess I harrowed my own feelings to if that is an acceptable reason to ask for grace.

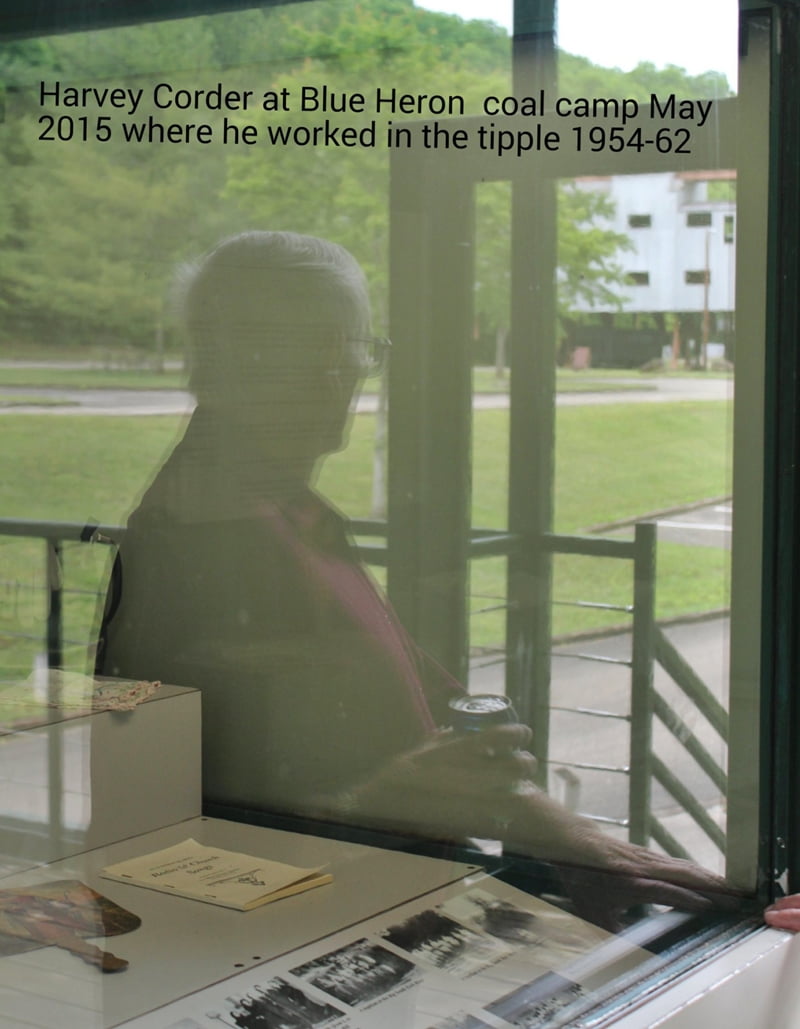

You all might care to know I submitted the photo of Harvey reflected in the glass to the National Park Service for a contest they held. I never was told the outcome but I was sent a copy of the book “The Arches of the Big South Fork”. There was no cover letter so I am not sure what it meant.

Ron

Thank you for sharing your memories, the story is a true reflection of how the man lived, loved and pursued his life.

I jumped the gun in reflections 5 and assumed your Father=In-Law had already gone on. Sorry.

I’ll never look at Big South Fork ever again in the same way!

Yes, time and chance get us all. This last installment is quite a powerful statement on life and the tides of change. Perhaps it so poignant to me because I am so far in this journey of life. I lived part of my childhood in a paper mill town. It was powered by coal and the whole town was covered with coal dust. It even got in the house by somehow sifting through closed windows. Without the paper mill there on the river there would have been no town.

That was a hands on age. Now is a mental age with electronics and computers ruling. Times always change. Sometimes I wonder what will be next……

I guess we all are writing a book with our lives some put it to print others just memories, some you choose to remember others you don’t. My Mamaw is one book I hold close to my heart, I choose to remember her and the impact she left on my life, I’m glad she’s not here to see what this old world has become it would just break her heart and I couldn’t stand to see her that way, she was a God loving and God fearing strong women, the most kind gentle person you’d ever meet, was raised with nothing and left here financially with not much, but yet left so much for us to hold on to. I enjoyed all these series of writings, makes you stop and think about where your at and where you come from and where are you going with your life.