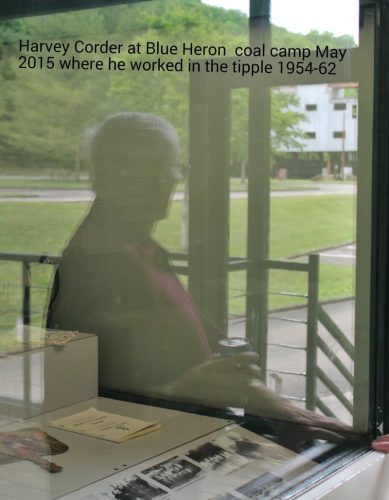

Today’s post is third in a series written by Ron Stephens about his father-in-law Harvey E. Corder and the Blue Heron Coal Camp located in Kentucky. You can see the first post here and the second post here.

Blue Heron is a ghost town now, first by abandonment and then by design. The Park didn’t put entire buildings back. Only the tipple is mostly whole. All the others were already gone, mostly burned by campers on the river. I still remember seeing a half-demolished house with bright pink sheetrock on the standing wall. Something about it was embarrassing somehow.

The buildings the Park chose to memorialize are what they call ‘ghost structures’. They are sort of like a pole shed except the ‘poles’ are steel and painted dark green. The floor is see-through green metal mesh and the railings are more green steel. Even the roofs are green. During the summer tourist season, everything blends into the trees and more or less disappears. The Park wanted to make a point of what I’ve learned by living it and what Solomon wrote a very long ago; time and chance happen to us all. They don’t say it direct like that. They want you to think about it. You have to figure it out for yourself. I reckon it was their business. For the tourist who never knew it as a living place, maybe it works. For me, it is kind of salt in the wound. It was my life. But anyway here I am doing just what they planned for, better even than the tourists do or can.

I could have never been here. I never planned to be a coal miner. I never planned not to be. I just came here in a round-about way. Right after me and Gladys married I worked at Wright’s Dairy up on top on Tunnel Ridge. We had delivery routes we ran morning and evening. They called me ‘Chocolate’ because I liked the chocolate milk so. But it closed. I didn’t see that coming. The handwriting was plain on the wall, right in front of me all the time. We had fewer and fewer customers. One by one, they started getting their milk and butter at the store, driving to the store on the good roads the WPA made. Some were afraid of our non-pasteurized milk. Others wanted ‘store-bought’ as a sign of having moved up in society. Meantime costs of all kinds just kept going up. The last straw was a state requirement of pasteurization. We had to modernize or go under. Mister Wright made his choice and sold his cows. I was out of a job. I should have learned something then about how technology and progress and dollars and cents shape the future. I should have learned how people change. But I didn’t really learn those things.

As it was, I was the son of a miner. Dad was the first generation off the farm. When I was a boy, Dad worked at old Barthell, just down the river and up Paunch Creek, only a few miles away. We lived in one of those old unpainted board-and-batten houses on the Barthell Rocks and got our water from a spring under the cliff. People walking up and down the Rocks passed right by the side of our house. I went to school on the west end of the camp, down by the creek and the tracks. At recess, we played on the slate dump the school sat on. I remember we played ball against the school here once, before there even was an Eighteen mine or tipple or a Blue Heron post office. My buddy and me made it up that if one of us hit a home run the other one would buy him a pop. He thought it would be him. But I hit the home run and he had to buy me one.

After the diary closed, I naturally put in for the mines. That was what young men did who wanted to stay in the county. While I waited, I went up North, to Indiana. I had family there to help me get a start. There were plenty of jobs then, right after the war. Business was booming, making up for all the wartime rationing and doing without. Finding a job was easy. I had several in less than two years. I worked in a metal shop, a tire place and an ice cream plant. But I never liked Indiana. It wasn’t so much the place or the people. It was just never home. There were no hollers and no cliffs. The people talked different.

Then Dad got sick with cancer. I came back home to help out and to be around for his last days. I did not have a job to come back to; I was still counting on a way showing up somehow. I got my start working tipple then, up at Co-operative. I worked for a Mr. Granville Smith. Everybody called him ’Gran’. I think he had a coal lease from the Company. I never did know much about the details, just that I had a job.

Dad died in ’55 but the Company had hired me on the Eighteen tipple in ‘54. I thought I finally had it made. I had a steady, good-paying job with a real future. I didn’t even have to live in Eighteen camp. I could drive in. The road had been into the river holler four or five years by then. It was not like when I was a kid in old Barthell. There was no road down in there then. We had to walk out up the Barthell Rocks to the end of the WPA road or ride the train out; only we could not afford the train as a regular thing.

I rented a little house up on Worley Hilltop, out where the sun shone, out of the deep, narrow and dark holler, away from the noise and the dust. We lived next to my father-in-law Howard Worley on one side and my brother Calvin on the other. And we had room, and sun, for a garden on Howard‘s land. From the top of the Eighteen tipple I could see the big cliff at the end of the point out past our house. The same high cliff hung over old Barthell. But it was over twelve miles to the house around the road. This country is like that. Cliffs and hollers cut it up bad.

I remember I had to walk out of here once, in the big snow of 1960. We had over twenty inches. It was only about two miles to the house, walking the old foot trail up the gap of the cliff. It took me over two hours to make it; slipping and sliding, climbing over, under and around bowed-over trees with snow falling down my neck. I was soaked through and give out when I got home. I think I never again was as glad to get home. The next two days I was sore all over.

Life went on, after they closed here in ‘62. There for a time I was out of work again. I had to make do. Cutting pulpwood or staves or tie logs was one of our making-do choices here then. There has always been timber if you can get it. So I cut bugwood – pulpwood some call it – for making paper. It is cleaner than mining but still hard and dirty work. Best you can do is just make getting-by money. There is no getting ahead in it. But it was what there was. So I cut on family land down on Cooper Creek, where my great-great grandpa John was living when he was killed. A passenger train at Greenwood hit him in 1912.

Even cutting pulpwood will make you think. It is a parable in its own way. The burr pines (I’ve heard them called Virginia pines) grow in what were once plowed fields or pastures. Somebody worked hard and long clearing that ground, probably John or my great-grandpa William, He died young, most likely from internal injuries from a falling tree in the log woods. Then another generation let it grow up again, un-wanted and un-used.

I remember they were having a revival at Cooper’s Delight church (we just called in Cooper Creek) at the time and having day and night services. I would be working and I could hear them singing over at the church. Felt wrong somehow, to be working but I had it to do. That church is long gone now. Me and my son-in-law went and hunted up where it used to be once. We almost didn’t find it because there was nearly nothing to mark the place, only some small bits of window glass and pieces of the old red ’brick’ siding. We looked a long time and were ready to give up until one of us remembered how the church had sat alongside the road at the forks.

—-

Be on the lookout for the next part of the series “Reflections.”

Tipper

Subscribe for FREE and get a daily dose of Appalachia in your inbox

Make that “almost always”!

So few comments on such a excellent treatise. I almost have a response when anything Appalachian presents itself. It just blows my mind that other readers don’t at least acknowledge it. Maybe it’s just a character flaw in me.

Tipper,

We went to Canton about once a year to Visit Fay, Mama’s sister, and Archie and the kids. Archie was a Boss at the Canton Plant called Canton Fibers then. It smelled terrible, almost as bad as the Inka Plant where they made nylon hose for women, before you get to Asheville. Me and Harold was riding in the back and he accused me of letting one, and it stunk something awful. Well, Daddy stopped the car, Peeled our Heads and proceeded on. ( Afterwards, he told us that’s just the Canton smelled. ) Daddy worked with Rocks on houses and his hands were Tough.

After we got to Faye and Archies, we didn’t notice the Smell so much and went playing with the rest of the Kids. I remember asking Clay, the oldest boy, about the smell and he said, ” You don’t notice it once you’ve been here for awhile.” Wade was my age and Arthur was still small, Marlene was in High School and Gladys had finished. (Gladys and Faye came to Harold’s Funeral Viewing )

…Ken

As I read the comments, it is so interesting to see what others found of interest in your story. You are indeed descriptive, and I find I must slow down my reading to take it all in. As the news paints the coal mines and miners sometimes as a miserable lot, I just don’t get it! I remember all the neighbors and friends who seemed to really enjoy their life blissfully unaware that many others did not live that same lifestyle. Life did not seem hard, and that time had so much of what we lack now. Of course I was looking through the rose colored glasses of childhood.

Unlike your Blue Heron coal camp, the coal camp where I lived as a child sold the houses and a few remain today painted and kept up. The small church still stands with a fresh coat of paint. There are even a couple of really nice large houses on the hillside which I imagine may have been built for the mine bosses. What does not remain is the tipple and the Company stores. A trip back not so long ago, and I drove up the holler to try to catch a glimpse of where the old tipple once stood. I wanted that connection with my Dad’s younger days and where he spent them; a tipple where my Dad put in many long hours. All that remained were remnants of coal that had slid down the hillside. I passed old homeplaces where all that was left were the flowers still growing after all those many years ago. Progress I suppose was the many small buildings that had been erected for the many ATV riders who use these mountain trails in the Summer. The coke ovens are still visible through the high weeds, but the nature is gradually reclaiming them. I am not sure why I am still drawn to make trips to see the remnants of McDowell and Greenbrier Holler in an area they call Northfork Holler. If we move away, maybe we still think we can go back and find some of the pieces of our lives. All I know is it was who we were at the time, and remembering it is therapeutic. When I worked I traveled through one such coal camp that was still populated, and I have never seen so many lights and decorations on porches and houses for the Christmas holidays in my life. Those warm colorful lights represented to me the heart of the old coal camps, and truly were a joy to behold on an otherwise bleak landscape. Thank you, Ron Stephens, for your stories that brought so many memories to my own mind. I will look forward to your next writing. Thank you, Tipper, for allowing others to give us such wonderful stories about parts of Appalachia we rarely have the good fortune to read about.

I remember that snow of 1960, we were out of school for weeks and the snow kept piling up. It stayed cold so it didn’t melt and the snow went on for weeks. I loved being out of school.

We lived in a paper mill town and it was a lot like a coal town. It was little and dirty with smoke and ash always in the air. It was a way of life. We didn’t think about it, it’s just the way it was.

I remember how Canton used to be. The plume of smoke and acrid smell made one think that Satan had opened his windows and was airing out the place.

My family thought it smelled like bread and butter! LOL!

Though they did object to the soot that sifted in through ever crack and window.

I’m really enjoying Rons’ writing of his Father-In-Law Harvey E. Corder. The Blue Heron Coal Camp was already a park and the Big South Fork Of The Cumberland River were places to visit and to fish. The river is a beautiful and dangerous place to fish with many rapids but we enjoyed it.

Ron mentioned the old church that is long gone and I thought of our old church that was torn down when we built the new one. Something about that just don’t seem right.

Ron you taught me a new word. I’ve never heard Virginia Pine called burr wood. We always called it Black Pine.

Is that what we call Virginia Scrub?

Ed and AW: Virginia pine probably has more common names than just about any other native American tree. Among them are scrub pine, old field pine, burr pine and another politically incorrect name. Those are just ones I know of offhand. I’m sure it has others, including – as you said AW – black pine A common thread is that they usually refer to its being very limby, knotty, bearing cones at a very young age and retaining them for years and years, just as it does the dead limbs.