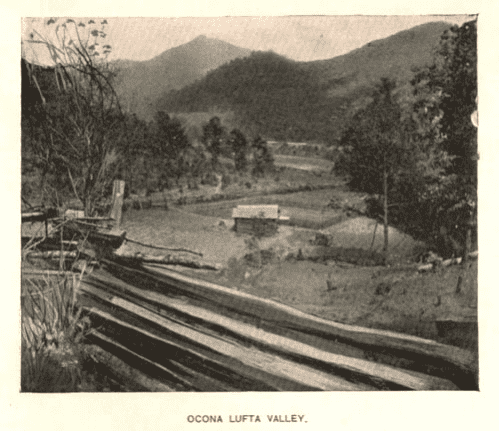

Today’s post offers a peek at the landscape which surrounds-The Lufty Baptist Church (also commonly called Smokemont Baptist Church). Below you’ll find three separate sources who each knew or know the area intimately-2 from the past; 1 from the present.

—————–

According to Western Carolina University’s Digital Collection: Travel in WNC:

In their 1883 book, The Heart of the Alleghanies, Wilbur G. Zeigler and Ben S. Grosscup related their impressions of travel from Bryson City, N.C., then known as Charleston, to Cherokee, N.C., then called Yellow Hill. Their route took them down the Tuckasegee River to the Oconaluftee River, and they following the latter river to Yellow Hill.

Two hour’s ride through the sandy, but well cultivated valley of the Tuckasege brought us to the Ocona Lufta. From this point the road follows the general course of the stream, but, avoiding its curves, is at places so far away that the roar of the rapids sounds like the distant approach of a storm. At places the road is almost crowded into the river by the stern approach of precipices, and then again they separate while crossing broad, green, undulating bottoms. . . .”

– Wilbur G. Zeigler and Ben S. Grosscup, The Heart of the Alleghanies (1883), pp. 37 – 38.

—————–

The book, Highland Homeland: The People Of The Great Smokies, written by Wilma Dykeman and Jim Stockley offers the following details about the terrain of the Ocona Lufta Valley:

By far the most ambitious road project was the Oconaluftee Turnpike. In 1832, the North Carolina Legislature chartered the Oconaluftee Turnpike Company. Abraham Enloe, Samuel Sherrill, John Beck, John Carroll, and Samuel Gibson were commissioners for the road and were authorized to sell stock and collect tolls. The road itself was to run from Oconaluftee all the way to the top of the Smokies at Indian Gap.

Work on the road progressed slowly. Bluffs and cliffs had to be avoided; such detours lengthened the Turnpike considerably. Sometimes the rock was difficult to remove. Crude blasting-complete with hand hammered holes, gunpowder in hollow reeds, and fuses of straw or leaves-constituted one quick and sure, but more expensive method. Occasionally the men burned logs around the rocks then quickly showered it with creek water. When the rock split in the sudden change of temperature, it could then be quarried and graded out. Throughout the 1830s, residents of Oconaluftee and the nearby valleys toiled and sweated to lay down this single road bed.

The desire and effort to conquer the wilderness also prompted the establishment of churches, and to a lesser extent, schools. In the Tennessee Sugarlands, services were held under the trees, until a small building was constructed at the beginning of the 19th century. The valley built a larger five-cornered Baptist church in 1816. Prospering Cades Cove established a Methodist Church in 1830; its preacher rode the Little River circuit. Five years later the church had 40 members.

Over on the Oconaluftee, Ralph Hughes had donated land and Dr. John Mingus had built a log schoolhouse. Monthly prayer meetings were held there until the Lufty Baptist church was officially organized in 1836. Its 21 charter members included most of the Turnpike commissioners plus the large Mingus family. Five years later, the members built a log church at Smokemont on land donated by John Beck.

—————–

Don Casada, who has studied the area encompassed by the Smoky Mountain National Park extensively, had this to say about the water drainage of the Ocona Lufta Valley:

Then at the Ravensford area, the Luftee and Raven Fork join. According to some drainage area measurements that I made a few years ago, at the point where they join, the area that feeds Raven Fork is about 80% of that drained by the Luftee above their junction. But according to my eyeballs, Raven Fork has more volume. Raven Fork is fed by waters that fall as far east as Balsam Mountain, which is the western edge of the Cataloochee Valley.

This is probably way more than you want to know, but here’s a way of maybe quantifying its size: The Luftee drainage area (including that of Raven Fork) within the boundaries of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park is right at 100 square miles, which is more than 50% greater than the area drained by Cataloochee Creek and more than twice the area drained by Hazel Creek. (both Cataloochee and Hazel Creek have been mentioned in previous Blind Pig articles).

Below Ravensford (visitor center area), which was the area of Swain County that was first settled by white folks, the Luftee is a relatively peaceful stream, but it is fed from some of the most rugged terrain of western North Carolina, particularly on the Raven Fork.

As you and some of your readers know, together with Wendy Meyers, I’m researching old home places in what is now the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Something that the two of us find both intriguing and inspirational is the distances and terrain traversed by folks to attend worship services.

Based on known home locations of some of the members listed in “Ocona Lufta Baptist Pioneer Church of the Smokies” by Florence Cope Bush, it is certain that folks were coming from at least 3 miles away. They came from well up Bradley Fork and above Collins Creek to the north. And they came from feeder streams that flowed from both east and west into the Luftee down below (south) of the church such as Couches, Tow String, and Mingus Creeks. Miles alone don’t tell the story. Some of these folks lived well back up these feeder streams in areas where even wagon travel was unlikely (sled roads were common), and there was hundreds of feet of elevation change involved.

It is highly likely that most of these folks came to church on foot, and they’d have come in all sorts of weather. Today we’re apt to grumble about having to walk from the house to the car when it’s drizzling a little rain.

The more I study these folks, the more amazed I am at their perseverance, strength, make-do intelligence, and right-mindedness in terms of the priorities of life.

—————–

The Ocona Lufta Valley was and is a rugged area of Western NC. If you’d like to see video footage of the whitewater of Ravensford check out this video on Youtube. The video actually ends at about 2 minutes and 50 seconds-but the song being used for background music plays the whole 4 minutes and 27 seconds. *Update: Tipper, the area where the kayaking video is shot isn’t Ravensford – it is on the Raven Fork.

The two names are connected, of course, but there is also an important distinction.

The Ravensford area lies close to the mouth of the Raven Fork of the Oconaluftee, and I’m sure that at some point in time there was an actual ford in the lower area. I’ll have to do some digging to see what I can find there. Ravensford is the broad flat bottomland section where the Cherokee High School now sits. That area was once the location of the Ravensford lumber mill, a huge operation. It was formerly in the park, but is now part of the Cherokee Indian Reservation – as is several hundred acres on the west side of the Luftee below the park entrance.

On the other hand, Raven Fork is the name of the stream which runs by the Ravensford area. It is a relatively sedate stream as it passes there, but as the video shows, anything but sedate about ten miles above. Those kayakers are in what is called the Raven Fork Gorge which is, as you can gather from the video, very rugged territory. There’s a section in the gorge where the 40-ft topographic map lines are so close together that you can’t tell one from the other.

Tipper

Sources:

1. Photo: WCU Digital Collection Travel WNC

2. Don Casada

3. Highland Homeland: The People of the Great Smokies: Author: Dykeman, Wilma; Stokely, Jim. This item is in the public domain. Book contributor: Clemson University Libraries

This is truly an awesome post. I’d love to walk through and see all of that. Thanks for the info and post.

How interesting to study all the old homesteads in the area. When I use to walk through the Reedy Creek Park/Ebenezer Park area in Raleigh, I always wondered about the old homesteads that had been evacuated to build that area, and why – because where these homesteads once stood is readily apparent, if not for the cemeteries dotted here and there, then by the odd beds of daffodils that bloom in spring, the rose bushes later in the year or the magnolia trees that once stood before these homes, then certainly by the remains of brick and stone foundations that are still there. I’ve always wondered why these homesteads were cleared for that area, how many souls were once nurtured there and how many hearts were broken when they had to leave – simply because one government or the other said so. because it’s a beautiful area I would never have wanted to leave had I had the choice.

God bless.

RB

<><

Bill-since Zeigler Grosscup were writing a detailed account I agree they should have gotten it right : ) But I think other folks just use the down or up without thinking whether the location is up or down in elevation. They are just using the words in relation to how they picture things in their mind-at least thats why I use them-like when I go down to Franklin : )

Blind Pig The Acorn

Celebrating and Preserving the

Culture of Appalachia

http://www.blindpigandtheacorn.com

Zeigler & Grosscup would have traveled up the Tuckasegee to the confluence of the Oconaluftee not down if traveling from Charleston (Bryson City). I am still amazed how many who “ain’t from round here” fail to relate the Up & Down by looking at the way the rivers flow. Just a couple of weeks ago I had a flatlander tell me he had “gone down to Sylva”, we were in Bryson City at the time. I pointed out to him that most natives of the area realize that water runs down hill and not up.

Very nice post to read. Old time photos and the stories that go with them.

These are stories of true pioneers who helped to develop our precious land to use it to its fullest worth. I am really eanjoying these historical scripts.

I truly enjoyed starting my day with such an intimate narrative of The Smokies, her magnificent waterways and those who traversed them!

Yes, “intriguing and inspirational,” and also “informative and educational,”–thanks for postings from older writings and from Don Casada! And for the Blind Pig author to coordinate and post it all! I, like Don Casada, am amazed at the dedication and example of our ancestors to establish churches under difficult circumstances and moreover to make the teachings they believed and practiced so much a part of their lives! I hope the next time we’re tempted to “not participate” or to have some other excuse for non attendance, we will remember those who willingly walked three or more miles to worship! Cold on the way, and far…and sometimes cold even in the log church house, but warmed by the love of God and the Spirit that held them and motivated them!

I am descended from both a Samuel Gibson and a John Carroll. Samuel’s son, John Stewart Gibson, married John Carroll’s daughter Mattie. One of their daughters Happuch Matilda “Happy” Gibson was my Great Great Grandmother. If these are the same two men mentioned above, I would be Happy to learn that too.

Tipper–From a fisherman’s perspective, there’s no more rugged area in the entire Smokies that the gorge on Ravens Fork (sometimes shown on maps as The Gorges). At places the stream narrows down between sheer rock faces on either side and it is virtually impossible to get out of the creek. You continue upstream by wading or even swimming.

Similarly, higher up on the stream, while it lacks the rough and precipitous drop of the gorge, there are no maintained trails above the one which leads from Straight Fork (a feeder of Raven Fork) over to Enloe Creek. It just traverses the drainage and crosses the ridge, goes down Chasteen Creek drainage, and ends up at the Bradley Fork Trail.

Above Enloe Creek in the Raven Fork drainage there is no maintained trail, but the Three Forks area in the headwaters is a place of virgin timber and surpassing beauty. You can read about it and even see photos in Tom Alexander, Jr.’s wonderful book, “Mountain Fever.”

Another indication of the ruggedness of the area is the fact that the old trail (long since abandoned and apparently so overgrown today it is almost impossible to find) went down by way of the aptly named Breakneck Ridge. Once you travel that area you realize that our mountain forebears had a real aptitude for place names.

As for the kayakers, and here I may raise some hakcles–theirs is an ongoing exercise in idiocy which I fear will, sooner or later, end in tragedy. Also, if there is an accident in The Gorges getting the victim out will be a monumental task.

Jim Casada

http://www.jimcasadaoutdoors.com

Tipper, the area where the kayaking video is shot isn’t Ravensford – it is on the Raven Fork.

The two names are connected, of course, but there is also an important distinction.

The Ravensford area lies close to the mouth of the Raven Fork of the Oconaluftee, and I’m sure that at some point in time there was an actual ford in the lower area. I’ll have to do some digging to see what I can find there. Ravensford is the broad flat bottomland section where the Cherokee High School now sits. That area was once the location of the Ravensford lumber mill, a huge operation. It was formerly in the park, but is now part of the Cherokee Indian Reservation – as is several hundred acres on the west side of the Luftee below the park entrance.

On the other hand, Raven Fork is the name of the stream which runs by the Ravensford area. It is a relatively sedate stream as it passes there, but as the video shows, anything but sedate about ten miles above. Those kayakers are in what is called the Raven Fork Gorge which is, as you can gather from the video, very rugged territory. There’s a section in the gorge where the 40-ft topographic map lines are so close together that you can’t tell one from the other.

Good Morning, Tipper. Your historical information is always interesting. And descriptions of our terrain bring me back to the dear Snowbirds. But your phrase “intriguing and inspirational” will lead me through my day (in the classroom).